Despite manufacturers reporting record profits, consumer goods prices often do not fall, and several interconnected factors explain this paradox.

First, companies tend to prioritize profit maximization over price reductions. When demand for products remains strong, firms have little incentive to cut prices even if their production costs decrease. Instead, they retain higher margins, rewarding shareholders and reinvesting in growth.

Second, global supply chains remain fragile. Even when manufacturers reduce costs in one area, lingering expenses from logistics, energy, or raw material volatility may prevent significant price cuts. For instance, shipping delays, fuel costs, or geopolitical disruptions can sustain elevated expenses that companies pass on to consumers.

Third, inflation psychology plays a role. Once prices rise, consumers often adapt to the new normal, becoming less resistant to sustained higher prices. Businesses are reluctant to lower prices for fear of devaluing their brand or setting new expectations that could be difficult to maintain if costs rise again. Instead, they may keep prices high while offering discounts, promotions, or smaller package sizes—a tactic known as “shrinkflation.”

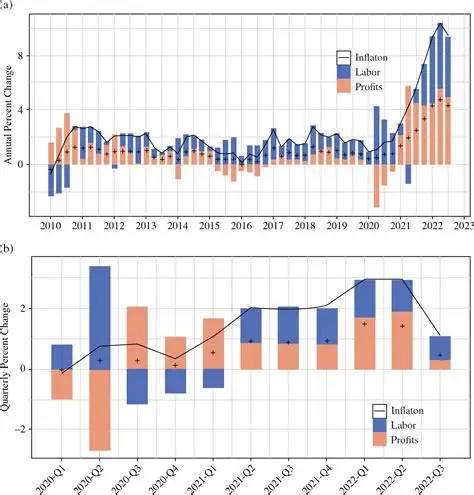

Additionally, wage growth and labor shortages increase operating costs. Even if material prices decline, higher wages in production, transport, or retail distribution can keep final prices from falling. Companies argue that maintaining higher prices helps them balance long-term workforce and investment commitments.

Another factor is market structure. In sectors dominated by a few powerful players, there is limited competition to drive prices down. These companies can collectively sustain elevated price levels without fear of losing significant market share. In contrast, highly competitive markets are more likely to pass savings to consumers.

Finally, many firms are directing profits toward innovation, sustainability initiatives, and digital transformation rather than lowering prices. While these investments may benefit consumers in the long term, they do not provide immediate price relief.

Therefore, even in times of record profits, consumer goods prices may remain high because of companies’ profit strategies, lingering supply-chain pressures, inflation psychology, rising labor costs, limited competition, and strategic reinvestment. Price stickiness, therefore, reflects not just production costs but also corporate priorities and broader economic conditions.

Leave a Reply